This is a revised version of the Minstrel 4th Quick Start Guide by George Beckett which has been updated to cover the Minstrel 4D.

Introduction

The Minstrel 4th and Minstrel 4D stand out from many other micros, in that they ship with Forth as their built-in language, rather than the otherwise ubiquitous BASIC. The Minstrel 4D is an expanded version of the Minstrel 4th, but runs the same code. So, herein, Minstrel 4th will be used to refer to both machines, except for cases specific to the Minstrel 4D.

Forth has several big advantages that make it a good match to the Minstrel 4th. First, it is fast, and, in particular, it is much faster than BASIC. Forth programs are compiled and interact with the hardware on a lower level than they do in BASIC, meaning it is not uncommon for a Forth version of a program to run ten times faster than the BASIC equivalent. Second, a Forth program is lean, using much less memory than its BASIC equivalent. This means you can write fast and compact programs for the Minstrel 4th, without having to resort to machine code.

Forth, however, has several idiosyncrasies that can deter those who are new to the language. First, Forth is a stack-based programming language. A stack is a relatively primitive data structure intended to provide temporary storage for a program. The programmer adds numbers to a stack in the same way a writer adds pages to a pile of paper. Numbers in a stack have to be accessed in a certain order; you can only access the entry on top of the stack, which is the most recent value added. To get to numbers lower down the stack (a number you added earlier on), you first have to take the values above it off the stack (those added after the number you want).

While a stack is primitive, it is much faster to access than program variables. In Forth, data is (usually) passed to and from routines via the stack rather than as parameters or variables, something that can be confusing to the uninitiated. Forth has a common notation for describing the state of the stack: the value on the top of the stack is called TOS and the next lower value on the stack is called 2OS.

Because the stack is so important in Forth, the language relies heavily on Reverse Polish Notation, in which parameters precede the procedures that act upon them. For example, in BASIC, you can set the print location on the screen using something like AT 12, 14. The equivalent expression in Forth is 12 14 AT. The parameters appear before the function (and there is no punctuation, other than spaces).

If you can get past these idiosyncrasies, you will find that your Minstrel 4th gives you lots of scope to indulge your passion for micro-computing and to create useful and interesting programs.

The Forth Language

At the heart of Forth is a 'dictionary' of procedures, which are referred to as words, encapsulating the functionality of the computer. You can see a list of built-in words, in the Minstrel 4th, by typing the command VLIST (or vlist, as words are case-insensitive on the Minstrel 4th). Looking at the list produced, there will probably be some words, such as PLOT and BEEP, for which their purpose seems obvious, but also many words for which it is not. In fact, words such as . and : may look more like punctuation than words. However, rest assured that they are words and it is important to remember that, when writing Forth.

The syntax of Forth is very simple, with programs being built up from sequences of (Forth) words and numbers, separated by spaces. There is no other punctuation in Forth except the space.

If you have the Minstrel 4th powered on, you can type the following simple expression (making sure to put a space between each element):

3 4 + 10 *

When you press Enter, the expression is copied to the upper part of the screen alongside the response 'OK', indicating success, but you will notice that no obvious answer is produced.

The field near the bottom of the screen, where you enter commands, is called the Input Buffer. When you press Enter, the Minstrel 4th looks to see what instructions are in the Input Buffer and processes them one by one from left to right. The first item it will come across in this case is the '3'. It will check to see if '3' is a word in its dictionary. It is not, so it will then try to interpret '3' as a number. This will succeed, so it will add 3 to the top of the stack (it will also move the item to the upper part of the screen, to indicate it has been processed).

The computer then checks if there is anything else in the Input Buffer. It finds '4' and again will interpret this as a number. It will add 4 to the stack and move it to the top of the screen. The stack now contains two values, 3 and 4, in positions 2OS and TOS, respectively.

The next item it finds is '+'. The Minstrel 4th will search its dictionary and find a word + that takes the top two items off of the stack, adds them together, and puts the answer back on the stack. The + will be echoed to the upper screen and the stack will now contain one value, 7.

Continuing on, it will add 10 to the stack and then execute the next word *, which will multiply the top two number on the stack and replace them with the answer, 70.

There are no more items in the Input Buffer, so the computer prints 'OK' to indicate it has successfully processed all of the instructions it has been given.

But where is the answer, you say? The answer is on the stack. If you want to see the answer, you need to ask the computer to print the value on the top of the stack and to do this you type the word . (that is, a full stop). This is another standard Forth word: it removes the top number from the stack and prints it on the screen.

Notice that Reverse Polish Notation helps here as it allows items to be specified in an unambiguous order. To write the same example in BASIC, would involve something such as (3+4)*10, using parentheses to ensure the individual calculations are completed in the correct order. In Forth, there is no need for parentheses: RPN means there is no ambiguity in the order.

The above example is not exactly earth shattering, but it does explain how Forth processes commands. Having cut your teeth with Forth, you might now try the apparently similar expression:

200 200 * .

---which does not produce the answer you probably expected.

If you are familiar with machine code, you may spot immediately what has happened. If not, I will explain. Numbers on the Minstrel 4th are, by default, held as 16-bit, signed integers, which can hold values between -32,768 and +32,767. If you happen to overflow this range (200 × 200 = 40,000, which is too big to fit in a 16-bit, signed integer), the answer will simply overflow and lose its most significant bit, leading to the wrong answer. However, the computer will not tell you this has happened: it will happily compute and report the wrong answer. This is a potential downside of a language like Forth. If you tried the same calculation in BASIC, it would have succeeded, though would have spent some time turning your inputs into its generic internal representation, consuming around five times as much memory and taking quite a bit longer to produce the answer. The trade-off for fast Forth arithmetic is that it relies on the programmer being aware of and checking for its limitations. By the way, Forth on the Minstrel 4th can deal with bigger numbers (and floating-point numbers, too) though this requires the use of different words, which are best kept until you know some more Forth.

Writing Programs

A key feature of Forth is the ability to define your own words, to supplement the standard dictionary. Forth programs are effectively words written by an end-user to encapsulate some function--anything from a platform arcade game through to a spreadsheet.

The easiest way to define a new word is by combining existing words. In this way, a program can be represented by a top-level word built up from other user-defined and internal words. This form of programming encourages a top-down approach and a large program could be made up of a number of layers of lower-level words.

To define a new word from other, existing words, you need to be aware of two Forth words, : and ; which switch Forth between compile mode and interpret mode. Consider the following Forth code

: double 2 * ;

We have seen * earlier, but the other words are new to us. This is a very simple word definition, which creates a new word, named DOUBLE. The : command tells the Minstrel 4th that you want to define a new word and the word immediately after is the name of that new word. Following on from that is the body of the new word, which is interpreted whenever you enter DOUBLE (or double). The word definition is terminated by the ; command, which returns Forth to interpret mode. Note that because : and ; are words, they need to be separated by spaces.

As you have probably guessed, DOUBLE multiplies something by two. However, as only one value, 2, is added to the stack, within the word, this means that the other value needs to be on the stack already.

When you type the command above, the computer will compile the new word into a fast, internal representation, ready to be used in the same way as other Forth words.

You can see that your new word is part of the dictionary, using VLIST. You should find that DOUBLE is the first word printed: it is at the top of the dictionary. (Notice that the Minstrel 4th always prints a word name in upper case, irrespective of the case you use when defining it.)

To test DOUBLE, you could enter something like:

6 double .

For words that you define, you can display the definition using the word LIST. Why not try this now. Notice that the Minstrel 4th will make an attempt to format the listing in an easy-to-read way. Notice, also, that LIST does not work for internal words: they are defined in a different way.

For this simple word, it is reasonably easy to work out what is going on, even if you come back to the word some weeks later. However, for more complicated words, it is useful to be able to add comments. To do this in Forth, you use two words ( and ), which indicate the beginning and end of a comment (though remember, they are words so need to be separated by spaces). Comment words can only be used when in compile mode (that is, when creating new words).

To update our word definition, for DOUBLE, we type EDIT DOUBLE. This will open the existing definition of DOUBLE in the input buffer and allow us to edit it, to something like:

: DOUBLE ( N -- 2*N )

( MULTIPLY VALUE ON STACK BY TWO )

2 *

;

For longer word definitions, EDIT will divide the definition into sections of around 12 lines long. Once you have finished editing the current section, press Enter to move on to the next one. Pressing Enter in the last section will end the editing session. Sadly, you cannot go back to the previous section in an editing session, so, if you need to backtrack, you will have to skip through the remaining sections and EDIT the word again (though you should read on before doing too much EDIT-ing).

You might naturally assume that the definition of DOUBLE has been updated, in the dictionary. However, this is not quite what happens. When the Minstrel 4th exits the editing session, it creates a new word at the top of the dictionary, which is effectively an edited version of the old word (which is also still in the dictionary). You can see this by entering VLIST, which will confirm you have two copies of the word DOUBLE.

Having edited a word, it is important to remember immediately to replace the old version, using REDEFINE--in this case, you would type REDEFINE DOUBLE. This will replace the old definition of DOUBLE by the word on the top of the stack (and also recompile any words that might depend on it).

The process for EDIT-ing and REDEFINE-ing words is a potential source of problems for someone new to the Minstrel 4th. If you forget to REDEFINE your word, you will end up having two copies and, worse still, if you go on to define more words, you will not be able to REDEFINE the earlier version, since REDEFINE expects the new definition to be at the top of the dictionary. In this case, the only solution is to use the word FORGET to remove all of the subsequent words and then use REDEFINE as you should have done originally. Say you had forgotten to REDEFINE DOUBLE, above, and, fuelled with enthusiasm, had gone on to write further words TRIPLE and QUADRUPLE. Then the top of your dictionary would look like:

To correct the issue, you would need to type the following:

FORGET TRIPLE

REDEFINE DOUBLE

: TRIPLE 3 * ;

: QUADRUPLE 4 * ;

In this case, the error is not too costly. However, in longer programs, it could become a very expensive mistake to fix. Because of this, it is wise to save your work frequently, as we will explain below.

Saving Your Work

When you turn the computer off, any new words you have defined will be wiped from memory. However, having spent time creating some new words, it is useful to be able to keep them for future use. Depending on whether you have a Minstrel 4th or Minstrel 4D, there are different ways to do this.

Both the Minstrel 4th and the Minstrel 4D can save to tape, in typical 1980s style. You can use either a cassette recorder or a modern-day substitute, such as a PC with a line-in jack. You need to connect the MIC socket of your cassette recorder (or LINE_IN of your PC) to the MIC socket on the Minstrel 4th, using a 3.5mm audio lead.

When you want to save your work, you use the word SAVE followed by the name you wish to give your work. For example:

SAVE MYWORDS

Before pressing Enter, you should press 'Record' on your cassette recorder/ PC, as the Minstrel 4th will immediately begin transmitting the data. It takes around 5 seconds per kilobyte to save your work (at 3.5 MHz). Note that, on the Minstrel 4D, if you have a suitable SD card installed, the dictionary will also be saved to the SD card.

Before powering off, it is worthwhile to check that you have saved your work successfully and, to do this, you use VERIFY. Connect the EAR socket of your cassette recorder (or LINE_OUT of your PC) to the EAR socket on the Minstrel 4th. Rewind the tape to just before the saved session and (continuing with our example) enter VERIFY MYWORDS. You can then play back the saved audio, so that the Minstrel 4th can check it agrees with what is in memory.

Similarly, to load your work back into memory from cassette (having connected the cables as for VERIFY), use

LOAD MYWORDS

If you have a Minstrel 4D, you can store your work onto a suitably formatted SD card. The Forth procedure is similar to saving to cassette, though there are no cables to connect and no Record button to press: if you are saving to the Minstrel SD card, the computer will automatically ensure the data is recorded to the card. During the save operation, the screen border will show thin, horizontal, black and white lines, which indicate that data is being written to the SD card. The computer will also automatically VERIFY the data, so there is no need to do that.

You load your work back into memory from the SD card via the built-in menu system, using 'Browse SD Card'.

If using a cassette recorder (or a PC sound card), it is worth noting that the Minstrel 4th and, to a lesser extent, the Minstrel 4D are hard of hearing. You will need to play back your saved audio at a high volume (though, thankfully, you will not hear it, as it goes straight into the computer's EAR socket). In my experience, you should set a tape recorder to play-back at around three quarters of maximum volume (or, on a PC, full volume is likely to be needed).

Trial and error is required to get a reliable process for saving and loading to cassette, so it is worthwhile to get to grips with this early on. This is a little easier on the Minstrel 4D, which will show lines on the screen border when loading the dictionary. You should adjust the volume to try to get even-sized black and white lines. You can also adjust the threshold volume on the 4D to support a wider range of audio sources (see the manual for details).

Next steps

This is the end of your quick tour of the Minstrel 4th (and Minstrel 4D). However, there are lots of other resources available to help you take your next steps.

The Minstrel 4th uses a variant of Forth, called Ace Forth, developed for an early 1980s micro called the Jupiter Ace. The Minstrel 4th is fully compatible with the Ace and runs the same monitor and Forth system as the Ace did. Software written for the Ace (and books about the Ace) should work on (and be relevant to) the Minstrel 4th. In particular, the original Ace user guide, called "Jupiter Ace Forth Programming" by Steven Vickers, is an excellent book for learning to program the Minstrel 4th. It was recently re-printed to celebrate the Ace's 40th birthday, so is relatively easy to find on retro-computing auction sites. Further, along with lots of software and other materials, you can find a PDF copy of the user guide on the Jupiter Ace archive website.

https://www.jupiter-ace.co.uk/

Hopefully, you will go on to have a great deal of fun programming your Minstrel 4th, and to become a convert to the Forth way. However, even if you do not, you will still be able to enjoy the wide range of software that others have written for the (Jupiter Ace and) Minstrel 4th.

You can find the original version of this article, and many more code examples and games in George's github repository:

https://github.com/markgbeckett/jupiter_ace

Advertisements

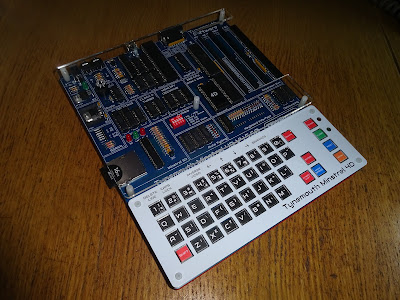

Minstrel 4D

The Minstrel 4D is available for preorder from The Future Was 8 bit. The parts are all here and the kits are currently being assembled to ship in the next few months. 2022-12-09 Update - Shipping Now

https://www.tfw8b.com/product/minstrel-4d-turbo-jupiter-ace-compatible-computer-kit

More info in a previous post:

http://blog.tynemouthsoftware.co.uk/2022/08/minstrel-4d-overview.html

Patreon

You can support me via Patreon, and get access to advance previews of posts like this and behind the scenes updates. These are often in more detail than I can fit in here. This now includes access to my Patreon only Discord server for even more regular updates.